- Home

- Jeff Ewing

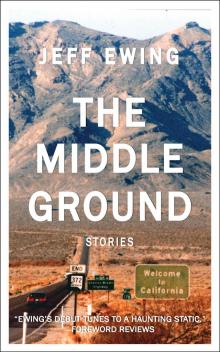

The Middle Ground

The Middle Ground Read online

The Middle Ground: Stories is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to current events, locales, and businesses, or to persons living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © Jeff Ewing 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Ewing, Jeff, 1956-, author

The middle ground : stories / Jeff Ewing.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77538-130-3 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77538-131-0 (MOBI).--ISBN 978-1-77538-132-7 (EPUB).--ISBN 978-1-77538-133-4 (AZW)

I. Title.

PS3605.W56M53 2019

813’.6

C2018-903325-8

C2018-903326-6

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Into the Void

www.intothevoidmagazine.com

For Diane and Romy

CONTENTS

Tule Fog

Silo

Ice Flowers

Double Helix

Coast Starlight

Lake Mary Jane

Crossing to Lopez

Parliament of Owls

Repurposing

The Middle Ground

Dick Fleming Is Lost

The New Canaan Village for Epileptics

Sognsvann

Barn Sale

Masterpiece

The Shallow End

The Armchair Gardener

Hiddenfolk

—Will you always remember me?

—Always.

—Will you remember me a year from now?

—Yes, I will.

—Will you remember me two years from now?

—Yes, I will.

—Will you remember me five years from now?

—Yes, I will.

—Knock knock.

—Who’s there?

—You see?

—DONALD BARTHELME, “Great Days”

Everything exists, everything is true, and the earth is only a little dust under our feet.

—W.B. YEATS, The Celtic Twilight

TULE FOG

WHEN PEOPLE TALK ABOUT CALIFORNIA, they don’t mean here. They’re talking about somewhere else—Palm Springs, Yosemite, Venice Beach, the redwoods—places that make for a good postcard, places where it wouldn’t be an insult to tell someone you wish they were there. The valley doesn’t fit on the same map. It’s flat and it’s hot, and the ground under you feels like something dead you’re walking on. In summer the news stations show people cooking eggs on the sidewalk, and the anchors laugh their asses off and shake their heads. In the winter it rains for a while, then the tule fog moves up from the river basins into town.

It starts slowly, the air thickening, visibility dropping, then it’s just there, so thick you have to walk with your hands out in front of you, fingers waggling like tentacles. It brushes up against you, coming on to you. But here’s the thing—and most people don’t know this—the fog has a false bottom. It hangs just above the ground, leaving a foot-high gap between its ragged hem and the skin of the valley floor. And in that gap, quietly and nearly bloodlessly, worlds are born and lost.

I watch it come in, then make my way across town to the neighborhood where I grew up, a once-desirable part of town that’s gotten long in the tooth. The roofs of the ranch houses sag on their rafters now that the kids are all gone and the heat and pressure they generated has been sapped out. I walk down too-familiar streets, the fog soaking my jeans, until I come to a weedy lot across from a tidy house with brown siding. Like a child with defective blocks, I start to rebuild.

I take the small slice of visible world and construct a plausible alternative. Cars roll by, legs scissor past, all of it moving slowly and tentatively in anticipation of my guiding hand. Voices and the sound of dishes being stacked filter in from a couple of streets over. Tonight, I think. This will be it.

There are six beers strapped across my chest in a bandolier. Once I settle in—my jacket rolled into a pillow, a silver space blanket spread out under me—I slide one out and pop the top. I listen to the report echo and note the sudden suspension of the small sounds you don’t notice until they stop. After a minute they come back, and I register their return one by one—the crickets ticking off the temperature, a mouse or a lizard tunneling through the grass, a rattlesnake curling and uncurling, its blood thick and sluggish. The fog amplifies it all, gathers it in lovingly.

“I haven’t slept in I don’t know how long.” A girl’s voice, as tired sounding as she claims. “Right. You’ll sleep … Come on. No. Come on … Why do I have to say it?”

I can see the tires of her car, the left front a little low, settled more than the others on the angled drive. Her feet emerge together, fall in unison onto the concrete and click off toward the house in impatience or anticipation. The door closes behind her with the same hollowness that her voice carries, compressed and EQed by the fog.

My high school girlfriend’s room was just off the garage there, the same room whose window lights up now with the half-assed glow of a compact fluorescent bulb. Some nights I’d coast my car to the curb and knock on the window, and Lisa would let me in through the garage. We’d sit on her bed and make out or listen to music. That was more than enough at the time—just imagine. She’d put on something slow and trickly and we’d listen until the sky started to lighten, the horizon pulsing beyond her back fence. Then I’d get back in my car and drive home. The air was like something sweet melting as I breathed it in through the window, my body tired and still vibrating faintly.

It took some practice to learn to drink lying on my back. It’s a talent, of sorts. Nothing I could get into college or a circus with, but useful all the same. Because it leads to this sense of the world above and the world below coming closer, hints of reconciliation. But there is also a pale overlay—like vellum on vellum—of something else, an uneasiness not far from fear. You can hear it in the click of shoes, the slow rhythmic tapping that gradually speeds up as it digs in.

Kids avoid my field; they think it’s haunted. They see lights moving through the fog, growing brighter, dimming. It’s just a joint or a cigarette, but they don’t know that. They’re kids. Unexplainable events are their gold standard. It’s only later that mysteries stop being prizes, that we fight against them with everything we have.

When I’m making my way over here from the light rail station, I take a route planned carefully to avoid the house I grew up in. Partly because it’s so run down now that I’m tempted to set fire to it, but mainly because it’s impossible not to look out from the yard and see what I saw when I was a kid, when there was nothing but new roofs and promise all the way out as far as you could see, all the way to the crest of the mountains. The trees were all small, our size, and the breeze passing between the houses was soft and clean as the air from a dryer vent. Now it’s sharp with dry rot and rank vegetation, and the mountains curl above the houses like an animal in mid-pounce.

I can’t see the mountains at the moment. Sometimes you can’t even see them in the daylight, but they’re there, jagged pieces of the earth pushed up at the edge of the valley like teeth breaking through gums. They define us by contrast, and we exaggerate their majesty to temper our poor reflections. Every day people go up there from the valley, and they come back changed—they claim to take something away that they didn’t go up with, even though it’s just an hour’s drive with no hardship to it. Th

ey’re better people for the trip, with a clearer appreciation of their place in the world. I don’t believe them, but I understand them. You couldn’t live here long without telling yourself that kind of thing.

The radio coming from Lisa’s former room sounds cheap and tinny, Ray Davies’ voice brittle as an old polaroid. I hadn’t pegged the girl for the classic rock type. Maybe it’s the only station she gets.

Lisa had a small sub-collection of albums, stacked off to the side of her bed in their own little library, whose binding theme was the moon. You don’t realize how many moon songs there are until you start grouping them like that. There are far more than necessary, probably because they don’t take much work. You look up and there it is, that blue shining harvest honey moon. You scribble a couple of verses about how waxen and dermal the light is, hash out a chorus expressing your awe at the magnificence and complexity of the world, then you sit back and wait for the royalties to roll in.

The kids eat it up, they think that’s romance. Which it is—for a time—and far be it from me to take that from them. But the moon’s been in reach for a long time now, and it’s tough to look up at it without thinking how we screwed ourselves when we stepped out onto it. How we went up there arrogant giants and came back petulant little shits.

A pickup slows and pulls to the curb. The door opens, feet exit. I see cowboy boots. Not working boots, manure-splattered and wrinkled like pork rinds, but soft, shiny boots. Street boots. The toes point in a little toward each other as though they’re about to start arguing, then they move off onto the curb and up the front steps of the house. Toward the slash of yellow light slipping out under the door, widening and spilling onto the stoop as the door opens without the boots even having had to knock. They’ve been expected.

A pair of bare feet slip over the threshold; the left foot rubs against the swell of the opposite calf.

“I’m sorry.”

“For what?”

“Whatever.”

“You don’t even know.”

“No. But I’m sorry anyway.”

I arc my empty beer can toward the house in a long, looping shot. It bounces once and rattles into the gutter. The four feet turn. The cowboy and the girl look out across a billowing plateau so insubstantial it can’t even support second thoughts.

Three doors down to the right is the house where my friend Tim used to live. We were in a band together in junior high, a terrible band, but kids used to stand in the doorway of his garage and listen to us anyway. Bobbing their heads while his dad’s tools rattled on their pegboard. It was a nice feeling standing up there with people watching, even if it was just fifth and sixth graders with animal backpacks and a sheen of candy residue on their faces. Lisa—as hilarious fate would have it—there among them.

Tim was in love with her first, and that’s probably why we stopped being friends later. She and I used to hear his car start up and pull out onto the street while we sat on her bed, the front bumper scraping every time. There was some anger detectable in the way he hit the gas at the stop sign. He could see my car from his driveway, parked where he wished his was, and I felt bad about it sometimes. I wished we’d found a way around it.

He died a couple of years after we broke up—after I proposed at a dumpy little inn in Napa and Lisa said no—in a car crash in the fog, rear-ended in his little MG by something much larger that crumpled him like one of the beer cans beside me and kept on going, shedding paint and metal scrapings as if shaking off bug splatter.

At his memorial service, his brother put together a slide show that ran on a loop at the back of the Legion Hall. I remember thinking how orderly his life looked, how it seemed mapped out from day one. Nothing was a surprise, everything went as planned—even the ending, which wasn’t true of course. It would have been truer if his brother had shuffled the pictures, let randomness define him so that he was thirty years old one minute and ten the next, screaming on the swings just after throwing his hat in the air at our graduation, standing on the slope of a glacier moments before taking his first steps. That’s how most of us live, really, bouncing around our lives like faulty pinballs.

Tim’s the one who gave Lisa the Van Morrison album. Moondance, for chrissake. I might not forgive him for that.

Sometimes I hear a dog barking through the fog. It’s always the same dog; he has a very distinctive bark. It reminds me of a dog I had when I was living with a woman who didn’t much care for me, a dog whose bark sounded uncannily like an attempt at speech, like a drunk trying to tell you something important. You’d swear that if you paid a little closer attention you could understand what he was trying to say.

When the dog was in the room, I found myself becoming circumspect, watching what I said. I chose my words carefully around him. When he wasn’t there, I tossed them off like baseballs I didn’t care if I lost.

“… never once asked me how I …”

“… how am I supposed to …”

“… all that bullshit about waiting for …”

“… you’re the one …”

The girl’s voice and the cowboy’s float out of the house and hover above me. His voice is, at times, mine, but at other times not. The fog separates the words from their context and they become nearly harmless. They could almost be taken back.

“… so goddamn sure …”

“… shut up …”

“… always you, never me …”

“… this is pointless …”

“… no shit …”

“… it is …”

“… I know …”

There have been other voices too, at other times. The girl has an older sister who got married about a year ago and moved out, and there are the twins next door. Sometimes voices drift over from other houses too, and from the street. I used to think I could collect them and paste them together like a scrapbook, that some hidden meaning would be revealed to me through them. The fog-filled snow globe would shake out and everything would be plain as day. Motives would be clear, judgments would be affirmed, and love would be requited.

“… I had everything. Now I have nothing …”

Go figure.

From time to time I’d hear about Lisa. She went on to become something of a celebrity, selling books and DVDs on late night TV and giving motivational lectures in towns around the country where people pronounce theatre “thee-ate-er.” I went to hear her once, when she spoke at the community center here. The room was large enough that I could slump in the back without being noticed, though once or twice I caught her squinting in my direction.

The title of her talk was “Moving On”—about how hard it is to get past what you need to get past for the sake of your personal growth, the hurdles you need to vault to become the best you you can be. She described how our past holds onto us like a web, with the bad things tangled up with good things so that it’s super tough to cut the threads. She had a PowerPoint and threw out a lot of anecdotes that I recognized from our time together, mixed in with others that must have been either made up or happened with someone else.

I can’t imagine her lecture helping anybody with real problems, though she evidently made a decent living at it. A lot of people are desperate for help, is the thing, and they want to believe it’s out there somewhere. When someone comes along claiming to have managed what they haven’t, and probably never will, they’re willing to listen. Once, anyway. I doubt there were many return customers. No one wants that kind of thing rubbed in.

The fog—worn through in places and thickened in others with an accretion like scar tissue—obscures and reveals alternately. That’s what it has to offer in contrast to unbroken vistas and breathtaking seascapes. If anything is lost, it’s the vastness of the night sky and the pinpricks of light that show us how small we are, that put things in perspective. But perspective is nothing more than a trick of the eye, a convergence of lines. It’s not music, or memory, or moonlight.

Lisa eventually married an attendee at one of her seminars,

a physical therapist from Boise. They had one child, a boy, before the little commuter plane she was taking from a seminar in Reno to a seminar in Turlock disappeared near Lake Tahoe. It took over a year for the wreckage to be discovered, which is hard to believe these days, with GPS and cell phones and the near impossibility of straying from the grid.

A lot of people from here volunteered in the search, skiing cross-country off into the voids that can still be found between highways. I went once myself, back in to a place she and I had skied to when we first started going out, a little valley between two high ridges. A creek ran through the middle of it that we could hear and sometimes see underneath the ice. It was a clear day, I remember, in January or February. A brand new year at a time when we believed in that sort of thing, in scheduled change.

The valley was beautiful and seemed undiscovered to us. We imagined ourselves as pioneers, cutting the first tracks to a new paradise. I don’t know why I thought the plane might be there, what exactly seduced me into thinking there might be some symmetry to life, that hers would come back around to me. As it turns out, a pair of backpackers found the pieces of the plane the following summer near Quincy, about a hundred miles off course.

Somewhere between the fifth and sixth beers the cowboy gets in his pickup and drives off. His headlights are swallowed up by the fog, and the sound of his engine fades almost immediately to nothing. Its diminution is not accompanied by the music of Crosby, Sills and Nash. He does not continue out of the frame, windows down and radio cranked, into a future of sloppy gestures and poorly regulated drinking. The girl does not—as fitting as it might be—cry oversalted tears and go on to describe to strangers with exaggerated nostalgia the tortuous course of doomed love.

Instead, the fog ticks onto dry grass and she locks the door and goes to bed.

The Middle Ground

The Middle Ground