- Home

- Jeff Ewing

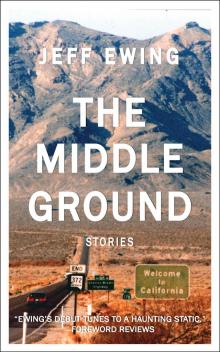

The Middle Ground Page 3

The Middle Ground Read online

Page 3

My dad’s already soaked. His old chamois shirt clings to his sunken chest. It lifts weakly when he draws a wheezing breath, then settles back into its wrinkles. He blinks against the rain running down into his eyes, but he still doesn’t look at me or say anything when I walk back across the pasture and into the house.

When you’re young, you don’t think you hold a place in the world, or that if you left anything would change. But it does. The whole world collapses around the event, as if a plug’s been pulled. My sister didn’t understand that. She still doesn’t.

I read the letter from Mendocino again, awed by its selfishness. They’re expecting their third child. They’re living happily up on the coast, and regret any sorrow or trouble they might have caused. Which is fine for them, but for us it doesn’t really help much. We’re still bogged down in the same mud, hoping every new storm’s the one that will either blow the sky clear or wash us away for good.

I turn on the gas in my father’s fireplace, put a couple of logs on for good measure, and throw the letter in. I don’t know who I’m protecting or punishing anymore, I just know the letter’s got no place here. In the end our lives are a cumulative thing, built out of every turn made or not made.

Say, for instance, you’re walking up a hill, following the same old trail like any other day. There’s only one way down at that point, back the way you came. But if you keep going past where you usually turn around, past where the path dribbles out into an estuary of animal trails, eventually another view opens up. Another way down. So maybe you keep walking. Across slabs of volcanic rock and bunch grass, over the two rivers, up to the base of the next mountains. By that point, it seems more sensible to just go on. So you do, on across the mountains that turn into row after row of mountains, through stands of timber and barren gullies, until finally you come to the ocean. You walk down to the edge, roll up your pant legs, and let the icy water drag your feet down into the sand. Then you scramble back up the bluff and lie down next to your chosen other. You fall asleep watching the water disappear over the side of the world, and when you wake up maybe the other way back is gone. Maybe the trail home through the hills isn’t available anymore.

I take a beach umbrella and a lawn chair out into the pasture and set up next to my dad’s chair. The rain’s hitting hard on the fabric.

“Damn cloud-seeding Russians,” he says.

The two goats come over and try to squeeze under the umbrella with us. I don’t know why they stay in the pasture. Only a few sections of the fence are still standing. There are huge gaps in between where a whole herd of goats could fit through. But they stay put. Not out of laziness, I’m sure, or consideration for us. It’s something else. But I have no idea what.

ICE FLOWERS

ANOTHER CALF HAD DIED. IT was Kauffman, his neighbor to the north, who’d found it. The calf had been dead at least a week; there wasn’t anything left of use.

“Okay,” Wilton said. “I’ll make a note of it.”

“It’s winter. You’re aware of that?” Kauffman said.

“I certainly am.” Wilton held out his gloved hand to catch a cluster of falling flakes. They melted almost immediately.

Kauffman patted him on the shoulder. “Keep an eye out, Wilt. Things die awful easy.”

It was an unnecessary warning to Wilton who, simply by turning ninety degrees to his right, could take in the graves of his wife, his daughter, and both parents on the little birch-tufted hill above the house. Death was a sure thing, yes, but it didn’t deserve the level of attention it received. Not in his reckoning.

When he was in fourth grade, he was dragged to five funerals in the span of three months. The Black Summer, he called it. Everyone sweating black stains through their black suits, black curtains on the windows, black fabric draped across the big chair his father slumped into at the end of the day. Wilton didn’t keep a single black thing in the house now. At some point—that summer or another like it—the two processes, dying and mourning, had switched places. Death became in his mind the aftermath of grieving; and of sun. So when the Black Summer gave way to the white night of winter, he welcomed it. He watched the snow come from the north, heard a thudding like horses as it broke against the house. On the windows, individual flakes hung briefly in stark outline before falling away. Without thinking, he ran out into it—the first blizzard of the year—with only a shirt and thin shoes, and nearly died. His father found him sitting against the side of the barn, his hands cupped in front of him full of snowflakes.

He held on to them as long as he could, but the heat of the house dulled their edges quickly, blurred their outlines and stole their singularity. Still, he knew there were more where they’d come from. The doctor’s announcement that he would lose two toes to frostbite was only of passing concern—there were more where those came from too.

Kauffman’s daughter, Flora, waved as Wilton passed along the section of fence that ran closest to their house. She was sitting on the porch with a book in her lap, content as could be even with the snow coming heavier and filling in the folds of the blanket draped across her legs. The influenza that had taken his wife and daughter had almost taken her, too. She’d been weakened by it, Kauffman said. Had to quit her job in the city and come home to recover. Wilton didn’t know how it could possibly be healing, sitting out like that in all weather.

He lifted his hand to wave back, then let it fall again. She wasn’t looking at him anymore; she was gazing up into the falling snow. When she stuck out her tongue to catch a snowflake, he looked away in embarrassment. He was familiar with the taste—it was nothing, or nearly nothing.

He herded the remaining cattle into the barn and pushed a hay bale out of the loft. He wasn’t much of a farmer, never had been, but you inherited most of your life, like it or not. The part you could decide for yourself was a small wedge you had to pull aside from the larger pie and save for later.

He kept his camera room at the outside temperature to prevent, or at least to slow, the ice crystals’ clumping impulse. Isolating them was tricky. They tended to be drawn to one another, to stick and blend at the slightest urging. His breath condensed around him as he set the apparatus up and moved a slide into position under the hopper. Lifting the release lever, he let a fine dusting of snow shower onto the glass. It looked like nothing at this stage—jagged white motes. He swung the camera into position, the lens set at the ideal focus, and tripped the shutter. There was a whirring click that disturbed nothing, the blink of an eye. Then quiet again as he slid another plate into position.

The darkroom, in contrast, had to be kept warm or the chemicals wouldn’t work properly. He tried to avoid the intrusive analogy to birth—the musty darkness, the images manifesting before his eyes—as the ice flowers bloomed, their petals and spines slightly distorted by the shallow layer of developer. Each sheet contained an orderly array of unique geometry he was the first to see. One by one, he hung them up to dry, then heated up a small pot of stew and sat down to his solitary dinner.

Was he lonely? He may have been at one time. But if so, he’d outlived it. If there was any remnant, it was only the trace hunger you feel when you stop yourself from eating your fill. The void is taken up soon enough by something else, and the next time you find you need even less.

In the middle of December, about a week before Christmas, it stopped snowing. The air turned still and cold, the sky went a naked blue. At night, the stars drifted slowly overhead like river ice breaking apart. Wilton found it easy to collect his crystals at first, sliding the top layer from drifts close to the house as if skimming cream. Soon, though, the crystals grew stale, losing their personality. Points drooped, edges dulled. He found himself having to go deeper and deeper into the woods to find good specimens.

There, he would shake a small tree by the trunk and catch the flakes on a panel of sheet metal. The sun glanced off them, lighting the facets like broken glass showering from the dome of heaven. He laughed, tried to think where in the world he’d gott

en that—one of his mother’s school primers, he suspected. The high-flown language she loved, so unsuited to their rough-cut lives. It occurred to him that Flora might have come across the line in one of her books. On his way in from collecting, he stopped at the fence.

“Are you familiar with ‘the dome of heaven’?”

She finished the sentence she was in the middle of, then looked up. Other than an occasional muttered greeting, it was the first real thing he’d ever said to her.

“I encounter it every day with wonder,” she said.

Her beatific smile unsettled him, and her answer was singularly unhelpful. He considered explaining his question a little more, telling her what had brought it on. But it would take too long, and the crystals in his collection case would suffer. He felt her watching him as he turned away; it put an odd hitch in his stride, he had no idea why—he’d been walking, after all, for years.

The thaw came in the early morning, with colder air close behind. Even deep in the woods, the snow melted and refroze, the crystals merging into hard communities of ice. He walked farther than he could remember having done before—even when he was a boy and would walk all day in a single direction, straight out across the plains or through the woods until the sun passed its zenith and he had to turn around again. His strides were longer now, he assumed; that was how he managed to pass out of his known territory on a day that was shorter than almost any other day of the year.

Fat drops of melt rained down on him from the trees; the snow underfoot was heavy and clung like mud to his boots. Here and there a smaller tree was bent nearly over, weighted down by the high water content. He came across a rabbit’s trail, and followed it to where the tracks ended in the middle of a clearing. There were no burrows in the snow, no limbs to jump to, no sign of any backtracking. The tracks simply stopped. A hawk was the likeliest explanation, if not the most satisfying. Wilton preferred to believe that the rabbit had found its way out somehow, back to the safety of the trees. One mad jump. The closest tree was twenty feet away.

The terrain became steeper. He climbed a ridge and followed its spine northwest toward where he could see a narrow plume rising. Someone burning slash, maybe, but he was well beyond even the farthest outlying farms. When the trees abruptly ended at the crown of the ridge, he saw the source—a hot spring tucked into a little notch in the hill. The steam was thick above the water, but thinned out periodically as a gust of wind drew it aside like a curtain. It was during one of these partings that he saw Flora stand up in the center of the pool.

He could see the lines of her body clearly—her breasts, pale and narrow, her waist too thin above her cocked hip. One side of her ribs seemed to be partly sunken in, an indentation he took to be a scar of some kind. She spun slowly with her arms out, setting the steam into a whirl around her, a benign tornado.

There was a beauty to the sight that troubled him, knowing it wasn’t meant for him. Still, he didn’t look away. At one point, as the cloud of steam began to close around her again, she leaned her head to the side and wrung her hair out gently. In that movement, worlds seemed to be undone. He’d seen something like it, he thought, in a book; his wife’s Golden Bough, maybe.

He was just at the edge of the trees, mostly hidden, but some movement drew her attention—his shifting from one foot to another, or a branch behind him shedding its load of snow. She wrapped her arms across her chest and dropped quickly into the pool. She had to emerge part way again to retrieve her dress, but Wilton had already turned away and started back by then.

Somehow he wandered twice from his trail, and had to range some way out before cutting it again. She was on her porch when he emerged onto his land. Steam was rising from her hair and her eyes were closed. He tried to pass silently, crossing to the far side of the narrow field.

“How was your walk?” she called across the muddy fringe of her father’s pasture.

“Fine.”

“Was it good both going and coming back?”

She said it with a wide smile, and afterward laughed with her face half-hidden behind her book. He thought she was laughing at him. He felt his face flush, and turned back toward his house. She called after him—“I’m sorry!”—but he kept walking, his feet stomping harder through the crust.

Lying in bed he tried, as he did every night, to recall his wife and daughter. And again, as every other night, he failed. He could call to mind a sweeping variety of ice crystals, thousands of them, but he couldn’t call back the familiar lines of their faces. He had only the one picture—the two of them together in a clearing somewhere, Elizabeth looking tired, and Dahlia beside her with the face of an old pioneer woman. They had aged so quickly, in no time at all. Then they were gone.

Perhaps it was this failing of his memory—which he took for a deeper failing—that had made him initiate, on his weekly trip into town, a catalog of faces. They were objectively different, nearly as divergent as ice crystals, but the indexing criteria were immensely harder to isolate. Where a crystal might be stelliform or palmate, plated, prismatic, dendritic, a face was … what? Something more than its relative shape or size, its beauty or homeliness. There was a component he couldn’t quite define. How a certain face could trigger a specific reaction in the viewer—distrust, happiness, anger—for no reason that he could name. His notebook entries were, even to him, cryptic and unhelpful:

Oval, eyes bluish shot with green, indifferent symmetry.

Animate block, deliberately obfuscate.

Dinner plate, blank, stained with scraps of last meal.

Belligerent nose, alcohol veined, judgmental chin with arrogant stubble.

He abandoned the project quickly. What was the point, really? None of it brought him any closer to understanding why some people stayed and others vanished.

Over the next days he worked harder and longer than usual, feeling an unexpected urgency. He photographed and developed nearly two dozen plates, working well past dark in the closeness of his darkroom. The onset of an ice storm outside hardly drew his attention. He heard pellets rapping against the side of the house and on the windowpanes in the kitchen. At one point, a loud cracking came from the north, from the direction of Kauffman’s. A tree branch succumbing, he assumed. There’d be work in the morning, wood to cut and clear. He’d help Kauffman, who always helped him, though he didn’t have the time for it.

A commotion woke him early—Kauffman yelling, wood splintering. He watched out the window as a pair of horses dragged the fallen porch roof away from the house and Henning, the fire department chief, pulled Flora out with the help of a younger man he didn’t recognize. They set her on a wide plank and loaded her into the back of a flatbed. Her hair hung out over the tailgate as the truck moved slowly through the snow. He saw Kauffman looking across at him, and backed away from the window.

A professor at the university had been pestering him for the last year about collecting his images into a manuscript. He told Wilton there was a great demand for it among meteorologists, physicists, even mathematicians. He could fill a gap in their knowledge, the professor said. So Wilton spent the rest of the day collating his prints, indexing them to his personal taxonomy. He wrote a short introduction in the last of the daylight, a paragraph full of excesses he thought Flora might have nodded her head over and smiled at:

The careful observation of the crystals’ felicitous structure reveals a far more elegant design than the naked eye could have alone imagined. Held in the hand, they are small and transitory, but here on film they bloom to their full grandeur. Gaze upon their multiform grace in awe—for their beauty not only illustrates the cold calculus of determinate nature, it expresses in exquisite form the history of their journey through the clouds to us. Who has not followed in his heart as they seem in a wind to rise even as they fall, and to flower at the advent of spring only in melting?

In addition to his wife and daughter, he tried that night to call Flora back. She eluded him likewise. She should have been fresh in his mind, but ther

e was only a kind of glow, a faint heat like the sun through drifting snow. He thought of her coming out of the water, her body steaming, the lines of her vibrating in the cold. She was looking at him, but she couldn’t see him. She leaned her head back and studied with some concern a stray cloud about to pass in front of the sun. When it did, Wilton knew, the world would turn again to ice.

He didn’t collect any crystals for a while. There wasn’t much point; everything was slick and frozen, useless. One afternoon, three or four days after the storm, he found himself by his north fence. He hadn’t planned it, and the discovery surprised and unsettled him. It was something that happened to old men.

The fence was still half-buried. He stepped over it and crossed the edge of Kauffman’s pasture. The porch roof had been hauled off to the side and broken up for firewood. Her chair was on its side by the corner of the house. It was frozen in, and it took some doing to free it. He set it on the porch and leaned it back the way she liked to sit, tipped on its hind legs.

“Don’t blame yourself,” Kauffman said from behind him. “I don’t.”

“No,” Wilton said, turning.

“Even if you heard it.”

“I thought it was a branch.”

Kauffman studied him. “You didn’t go look, though.”

“It happens all the time. You know.”

Kauffman hadn’t shaved lately, and he seemed to be leaning slightly, as if a wind were blowing from his side.

“I don’t know if she suffered,” he said.

“She never seemed to.”

The Middle Ground

The Middle Ground